When Claral Richards gave me this excerpt from a book called “Bananeros in Central America”, by Clyde

Stephens, I couldn’t wait to dive into reading. Once I began, I couldn’t put it down! This is a first hand story from a man by the name of Mark Trafton Jr.*, who came to Panama on September 10, 1928 to begin his adventure as a Woodlands Banana Farm Manager for United Fruit Company (which later became Chiquita). His account vividly describes what it was REALLY like for the pioneers who came from around the world to start the banana industry in Baru’ Panama. Let yourself be transported to this time in history and enjoy!

PART 1 – Introduction to Panama

Another drastic change in my life was arriving in Cristobal (Colon) in the Canal Zone on September 10th, 1928. At the company office there I was given a ticket on the Panama Canal Railroad to Balboa (Panama City) on the Pacific side of the Isthmus, a small cash advance, and told to report to the office in Panama City. There I met the company agent, Sr. Tomas Jacome (later the best man at my wedding!) who checked me into a hotel for a two-day stay waiting for transportation to Puerto Armuelles, up the Pacific coast, near the Costa Rica boundary. Not a very exciting stay in Panama City, being short of cash, walking up and down Avenida Central and admiring all the window displays of goods from all over the world. “Panama City”, the Crossroads of the World”, was well-named. One night was pretty wild, but not for me, with about 5,000 sailors in their “summer whites” on shore leave from some U.S. Navy ships transiting the canal. They literally took over the town, including all the Central Avenue bars and nightclubs, since the Panamanian soldiers (police) had wisely decided to take the night off!

My transportation to Puerto Armuelles was a small, beat-up old coast-wise schooner, the “Berta” which chugged along at a snail’s pace for four hot days and nights over smooth seas. The captain and crew of three rather young, ragged, dirty guys were surprised that I could understand and speak Spanish so they regaled me with wild seafaring tales of “The Panama Main”. The food was terrible except for a few fish they caught trolling. On the second day out I learned that the cargo was a load of dynamite, and caps, for the contractor building the government railroad from Puerto Armuelles to Progreso. Had I known that before I would never have boarded the “Berta”!

Approaching our destination I admired the beautiful Secas and Paridas Islands where, years later I would spend many happy days. The coastline was an unbroken vista of green tropical rain fores, a solid mass which, miles away, faded into a light blue haze of the high mountain range on the horizon.

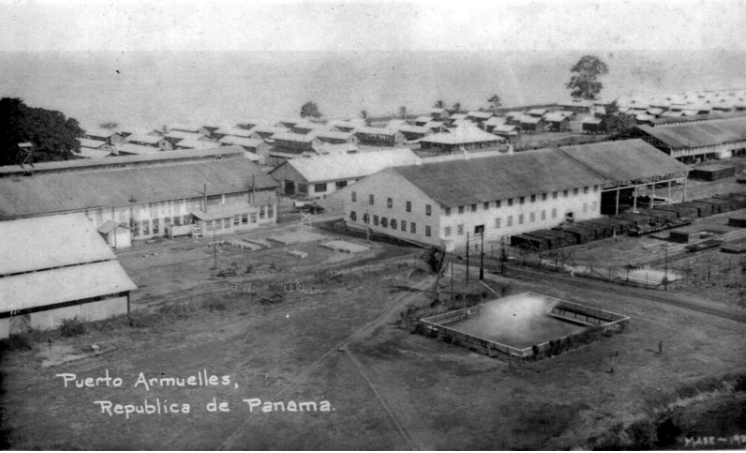

At Puerto Armuelles a small block of jungle had been cleared and a few labor camps, long narrow wooden buildings on stilts, had been built along with large bodegas or sheds for storage of equipment and materials, offices, a machine shop, and a small radio station and tower. The government railroad, only partially finished, a long narrow strip cut out of the jungle, stretched back several miles into the interior where the banana farms were to be planted, and on the eventually hook up with the existing railroad from David to Progreso.

The banana buildings in Puerto Armuelles and El Carmen (Silver City) to the Pacific Ocean in the 1920’s

There was a small cluster of native thatched palm huts along the beach where some of the local labor lived. The Company had commenced building the large steel wharf where, in a couple of years, stems of bananas would be loaded into ships for West-coast markets. When the “Berta” arrived late one afternoon , another coast-wise boat was tied up at the temporary landing where cargo was discharged by a crane, so they rowed me ashore in a small leaky dinghy which capsized in the light swell along the beach. From where I waded ashore, taking a few Saints’ names in vain, to commence my career as a banana cowboy. Fortunately my small wardrobe trunk and suitcase were unloaded later that night at the dock. My arrival had been announced by Morse Code from Panama.

I was greeted on the beach by a Company Panamanian lawyer, Licenciado don Carlos Bierbach, later a justice on the Supreme Court of Panama and a close friend of mine for all the fourteen years I lived in Panama. He had arrived there from Panama City a week before to study engineers’ maps of the company land acquisitions in the area. The first-class employees living there bunked bunked four to a room in what would later be labor camps. The temporary division headquarters was in a few old wooden buildings in Progreso, about 25 miles from Armuelles on the banks of the Chiriqui Viejo river where there had been a small sugar plantation and cattle ranch in the past. Access to Progreso then was by railroad from David, the capital of Chiriqui Province, a small city about 40 miles distant in the center of a large cattle raising area. Near David the small port of Pedergal accommodated coast-wise schooners from Panama City. There was no overland route until the International Highway was completed many years later – but an airport was built there by the United States Army during World War II. Eventually Progreso would be connected with the railroad then under construction through the rain fores (later banana farms) from Puerto Armuelles.

My first night in Armuelles I was assigned a bunk in a room with two American engineers and a drag-line operator. The nightly amusement was a poker game for big stakes which I could only watch. No money! The drinks the players shared with me I thought were awful. It developed they were Bay Rum and water! The Company had not yet been granted a license for sale liquor. However, a few weeks later hot beer (no ice or refrigeration) came on line and that was the staple drink for over a year except for an occasional bottle of the local Gorgona rum brought in by travelers from David. It wasn’t much better than the hair tonic variety!

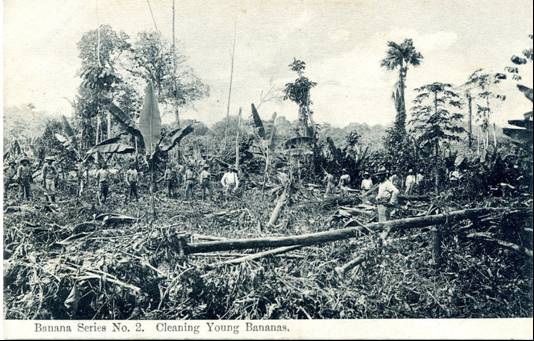

The schedule for me was to take over planting a “woodland” farm which was just underway in “Esperanza” but stopped for lack of labor. The native “Chiricanos” from the interior were “cowboys” and had no desire to work in the sweltering rain forest jungles, so the Company had to import labor from Nicaragua. While waiting for a shipload of those “axe and shovel men” to arrive I was assigned as Assistant Superintendent of the Material and Supply department in Armuelles, checking arrival and distribution of construction materials and equipment to the different engineering and drag-line camps in the jungle. Fortunately, that assignment only lased for six weeks before a boatload of “Nicas” arrived. About 200 real tough, but hard-working, men who were anxious to work for the relatively high wages in a new banana division as compared the the poverty-stricken situation in their country.

There was one experience I shall never forget during my short stay in Puerto Armuelles. A wharf stevedore, Dave Spence, and I took a Sunday stroll along an engineers’ narrow survey line cut through the jungle from the camp area up into what, once the forest was cleared away, would be the location of the main office, then the hospital, followed by the clubhouse and then the rows of residences for the first-class employees. We were well-armed, he had a rifle, a six-gun and a knife and I had a 45 automatic which I had bought from an engineer in my first payday there. As we walked slowly and laboriously along the rough “Piquette” sweating profusely, admiring the plants and occasional birds in the heavy fores, we suddenly “froze”. About 15 feet in front of us an enormous black panther (a rare species even then) had just dropped down from a large tree branch over the trail. The beautiful animal looked us over for a minute or two and then slowly moved away into the heavy woodland under-story of low plants and vines. Not a shot was fired – I couldn’t even move my arm to reach for the 45 – I felt as though my circulation had stopped. I have never been so scared in my life! Dave and I just looked at each other, we didn’t speak, we didn’t have to, as we slowly and silently retraced our steps along the trail back to camp where we took a shower and put on a change of clothes.

The 200 Nicaraguan workers, led by a guide, went by foot through the forest to Esperanza where they constructed two large barracones of poles and thatch which they cut in the jungle – their quarters for the next year or more. I went part of the way to Progreso on a work train and the rest on foot through mud and water along the remaining railroad right-of-way. My belongings went on a “tractor supply train” over a circuitous route, first along the beach for a few miles, then up the high banks of the Chiriqui Viejo river to to Esperanza – a two-day trip if it didn’t rain.

The 200 Nicaraguan workers, led by a guide, went by foot through the forest to Esperanza where they constructed two large barracones of poles and thatch which they cut in the jungle – their quarters for the next year or more. I went part of the way to Progreso on a work train and the rest on foot through mud and water along the remaining railroad right-of-way. My belongings went on a “tractor supply train” over a circuitous route, first along the beach for a few miles, then up the high banks of the Chiriqui Viejo river to to Esperanza – a two-day trip if it didn’t rain.

At Progreso I was given a horse and saddle, a pair of saddlebags with a few emergency rations and water, and told to follow the trail for 5 miles down the river to Esperanza. The answer to my doubts about following the trail was “the horse knows the way”. The horse was no polo pony but it was experienced in plodding through brush and mud. So, armed with my 45, which I had only shot a few times, I arrive sagely in Esperanza to begin life as a Woodland Banana Farm Overseer.

To be continued…

Click to continue reading: Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 2

NOTES:

*All photos were added by the editor of Visit Puerto Armuelles after researching the time period.

*Mark Trafton Jr was in Puerto Armuelles/Esperanza, working for UFCO, for 14 years and was an avid scientist as well. He contributed some of his research to a book in 1937 called “Tertiary and Ouaternary Fossils from the Burica Peninsula of Panama and Costa Rica” and the credit is given from the author as:

“I am also deeply indebted to Mr. Mark Trafton Jr. of the United Fruit Company, stationed at Puerto Armuelles, for much interesting Pleistocene, as well as Recent, material.”

* “Bananeros in Central America”, by Clyde Stephens, was published in 1989 and is currently out of print. There are copies in some libraries and a few available through collectors online.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this and look forward to more. Thanks for doing this.

So glad folks are enjoying reading about the history here. I liked it too, and have a bunch of new (old) stories I’ve come across since finding this one. I’ll be sharing many more interesting historical bits!

A very interesting read.

I just bought this book used on EBay for $4.99. There is one new for $124.95 and 2 for $4.98 and 14.95

I’ll try to nab the $4.98 book now – thanks!

This is the author of Bananeros in Centrral America, Clyde Stephens. Mark Trafton was my boss in my early years with United Fruit Company. He and I went from Golfito, Costa Rica, by rail car, crossed the international border at Puerto Gonzales, checked our passports and crossed to the Panama side. We had to switch rail cars because the gauge was different from the Tico side. That was April 1959. Our mission was to assess a severe insect problem. I was the new entomologist and Mark was the seasoned old banana man with so much incredible talent. Glad you liked his story in my book. Since that book, I have about 8 more written about the same themes.