This is the second installment in a series of re-prints of the first hand account of Mark Trafton Jr., one of the original Woodland Banana Farm Overseers in the early days of United Fruit Company in Barú. In this episode, learn about the housing and meals on the fincas. If you missed Part 1, please click here to read from the beginning:

Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 1

PART 2 – Esperanza (“Hope” in Spanish)

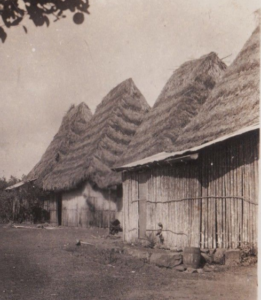

ESPERANZA (“Hope” in Spanish) was a clearing along the right-of-way of the future railroad. There were a number of manacca shacks for the overseers, timekeepers and foremen, a stable with about 20 riding mules, a mess hall and a medical dispensary, all palm-thatched. The labor camps, as described, were about a mile away toward the river where there was a “commissary”. All supplies and building materials arrived once a week on the tractor supply train.

My manacca shack was a new one, finished just a few days before I arrived. Furnishings were a “Tijereta” (a large folding canvas cot) with a mosquito “bar” (net), a small folding camp stool, a wooden bench, a galvanized bucket and a kerosene lamp. I added to those furnishings by acquiring a few empty wooden boxes at the commissary for storage. The shack did have a wooden floor – a few roughly-hewn planks laid on the bare ground

Upon arrival I was met by the senior overseer there, Bob Cover, a rough and tough, but kind-hearted bushwhacker, a Jamaican, born on a banana farm in Costa Rica. he too had a “45”, but on an ammunition belt with about 24 rounds of bullets. He greeted me with a handshake which almost floored me and invited me into his shack but warned me “don’t mess around with my woman”. His “woman”, Amy, was a young good-looking and very pleasant black Jamaican, also born in Costa Rica. She was the best “San Cocho” (a Panamanian version of chicken stew) cook I have ever -known!

They had a son, who turned out very well, and Amy stayed at Bob’s side for the rest of his life.

Other personnel in Esperanza were; Vernon Selby, dishonorably discharged from West Point for crowning an officer with a chair; Emilio Fabrega,~a Panamanian from one of the elite and top political families in the country; Ted Scott, a young Australian wanderer; Red Barkley, just -out of Stanford in California; Arnie Halldorson, a second-generation Icelander and an ex-marine from North Dakota; Hoy Crosse, a well-educated Jamaican; and Tubby Spence, from California, recently transferred from a banana farm in Costa Rica.

A mixed bag of guys the Superintendent didn’t know what to do with! In the other three districts, it was almost a family affair. Most of the farm overseers, as well as other executive employees in the division, including the Manager, H. S. (Hank) Blair (a Harvard graduate) had worked together for years and had just been transferred from the Almirante (Panama Atlantic coast) division which was closing down due to Panama Disease (Fusarium exysporum a soil fungus which killed out the Gros Michel commercial variety of banana plants).

It was standard procedure in the early days of the banana business, as Panama Disease wiped out a division, to move,”lock, stock and barrel”, to another location of virgin woodland, generally in a different country, and put in; an entirely new division which might last 10, 15 or 20 years, depending on soil susceptibility to Panama Disease.

The mess shack where the overseers, except Bob Cover, and timekeepers took our meals, consisted of a long wooden slab table with benches on both sides and a couple of kerosene lanterns hanging above the “table”. In the cocina (kitchen) to the rear were a large locally fashioned clay oven, an open barbecue-type grill, a large washtub for a sink and a collection of large pots and cast iron frying pans. Water was kept in some diesel oil drums which had been cleaned out. Some badly chipped china and glassware and an assortment of “silver”, probably from old company ships, graced the table. However, in spite of this foreboding description of the dining room, the food, prepared by an old black Jamaican man, was generally excellent and, at times, “epicurean”.

There was no refrigeration of any kind so, save for a few “tins” of imported goodies, everything was “fresh”, right out of the jungle or nearby rivers. With hundreds of workers felling the forest every day there was always an abundance of fresh meat, fish and fruit. The large labor camps had “hunters” whose only job was to supply their kitchens with food.

Some of the delicacies we feasted on almost every day were; the highly esteemed flesh of “tepiscuintle”, a large rodent the size of a small pig (this was one of the mainstays in the diet of the early Aztecs and Mayans); “chancho de monte”, wild boars (peccaries) the fed in large bands; pigeons; forest deer; chachalaca, pheasant-like birds; Crested Guan, large turkey-family birds; Tinamous, small ground birds; Perdiz, like partridges; wood-quail and many varieties of fish, and crocodile tail meat, secured by dynamiting large pools in the river: bushels of tender “hearts of palmll from the tall slender palmito palms; fruits such as Zapote, Caimito and, of course, bananas.

Rice and beans, brought in by traders from the interior occasionally were also staples as was the company-imported “bacalao”, whole salted and dried codfish fillets direct from Gloucester, Mass. I also suspect that when hunting was not too successful, our stews and soups might have consisted of macaw, parrot or toucan breasts and thighs, as well as some monkey meat now and then! The point is, we ate heartily, and well. There was one condition before each meal in the evening, the “dispensarian”, “Doctor” Smith, black Jamaican with the power to withhold the single shot of free grog, “Gorgona rum”, until each diner had downed a couple of ounces of liquid quinine to prevent malaria. I don’t know which was worse, the local Click to continue reading: Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 2rum or the quinine, but it was a ritual we all accepted.

Actually the taking of wildlife for food was not as bad as it sounds. As the forests were felled and planted to bananas there would no longer be a fit habitat to support them and, of course, there remained thousands and thousands of acres of virgin rain-forest along the coast after all the farms were planted. With time, in about 15 years, the forest too was destroyed by natives with their roving agriculture and production of charcoal. The railroad, and later a highway, allowed “civilization” to move in and, as elsewhere. that was the end of of nature’s grandest achievements, a pristine tropical rain-forest.

To be continued…

Click to continue reading: Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 3

NOTES:

*All photos were added by the editor of Visit Puerto Armuelles.

Thanks Debbie. I am really enjoying this.

Me too! I was so excited when I got the manuscript. It has actually led to more interesting history finds so I’ll be posting quite a bit more in the future.