***If you missed the previous installments, click on the links here:

1928: Parte 1, 1928: Parte 2, 1928: Parte 3, 1928: Parte 4, 1929:Parte 5, Parte 6, Parte 7, Parte 8, Parte 9

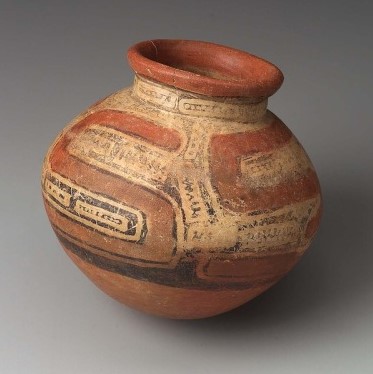

With a servant and an occasional baby sitter in the house, Harriet and I often played golf on Saturday afternoons (during all my years in the tropics everyone worked until 11 A.M. on Saturdays). On Sundays, we would walk in the jungle or ride a motorcar to the farms to join Bob Cover in digging Indian graves. We found many beautiful painted clay pots and bowls but never any gold artifacts, although many had been found in Chiriqui province. The Chiriqui Indian* antiquities pre-dated the Spanish conquest by several hundred years. On our weekend walks into the forest we became interested in collecting butterflies.

So that I wouldn’t be seen with a butterfly net, I always asked Harriet to carry it through town until we got into the woods, and again when we returned back through town! In that lush tropical main forest there were lots of beautiful species and we collected many, including some of the large blue morphos and “owls”. I would mount and pin them into glass-topped trays. Since I had no idea what the scientific names were (there were no “guide books“ in those days) I would airmail a series of each type, securely pinned in boxes, to Dr. Gertsch, Assistant Curator of Lepidoptora at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. They were glad to get those Panamanian species for their collection, officially acknowledging them, and returning one specimen from each series to me with its scientific name. I also photographed the best one of each species in black and white and then made life-size enlargements which I would hand-color with special oil paints.

So that I wouldn’t be seen with a butterfly net, I always asked Harriet to carry it through town until we got into the woods, and again when we returned back through town! In that lush tropical main forest there were lots of beautiful species and we collected many, including some of the large blue morphos and “owls”. I would mount and pin them into glass-topped trays. Since I had no idea what the scientific names were (there were no “guide books“ in those days) I would airmail a series of each type, securely pinned in boxes, to Dr. Gertsch, Assistant Curator of Lepidoptora at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. They were glad to get those Panamanian species for their collection, officially acknowledging them, and returning one specimen from each series to me with its scientific name. I also photographed the best one of each species in black and white and then made life-size enlargements which I would hand-color with special oil paints.

Doing all that photo darkroom work in a blacked-out laundry room under the house in the tropics, with no air conditioner or electric fan (which would kick up a lot of dust) was a hot job! All that photo work took hours and hours of my spare time. I had almost 150 life-sized colored pictures of my collection, but they were all lost in the flood of 1954 in Honduras.

On those butterfly collecting trips I eventually learned that it was easier to get perfect specimens by collecting the caterpillars and “hatching them out” at home, rather than frantically swiping at them with a net. However, I never found the larva of the beautiful and rare glossy metallic blue morphos until many years later at Lancetilla in Honduras. They were 6″ long, banded red and brown, 1 inch thick, gregarious caterpillars which fed at night and spent the daylight hours huddled together in an almost solid clump in the highest treetops!

We had many thrilling experiences on those collecting trips, snakes, army ants, all kinds of birds (this was before my “birding” days), orchids, beetles including the rare “gold bug”, many small animals and some big ones. Once, while walking in the bottom of a deep ravine, a mountain lion came tumbling down from a couple of hundred feet above us. It had jumped at something and missed and when it hit the bottom, just a short distance in front of us, I don’t know who was scared the most – the beast or us.

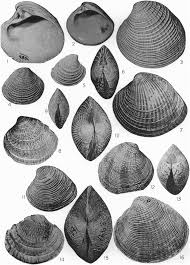

On one of our weekend walks in the rain forest, we came across an outcropping of fossil shells in the banks of the nearby Rabo de Puerco (pigs-tail) creek; well-named because it was really crooked! We collected a lot of them on several trips and kept them in a box at home. A friend, Robert A.Terry, a geologist exploring in the area for oil companies, saw the collection one day and told us we had discovered a deposit of Pliocene and Pleistocene marine fossils. He contacted an associate, Dr. Axel A. Olsson, Associate Curator of Mollusks at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, an authority on the subject, and told him of our collection. Dr. Olsson was very excited about this and arrived in Puerto Armuelles a few weeks later.

On one of our weekend walks in the rain forest, we came across an outcropping of fossil shells in the banks of the nearby Rabo de Puerco (pigs-tail) creek; well-named because it was really crooked! We collected a lot of them on several trips and kept them in a box at home. A friend, Robert A.Terry, a geologist exploring in the area for oil companies, saw the collection one day and told us we had discovered a deposit of Pliocene and Pleistocene marine fossils. He contacted an associate, Dr. Axel A. Olsson, Associate Curator of Mollusks at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, an authority on the subject, and told him of our collection. Dr. Olsson was very excited about this and arrived in Puerto Armuelles a few weeks later.

We took him to the “digs” where he collected for several days and then returned to the States with boxes of specimens, including most of ours. Later, in 1941, he and Dr. Pilsbry, published, in the Academy Proceedings Vol. XCIII, an account, with illustrations, of the collection which included “Chione Traftoni“, an extinct species new to science. “The Type of this species (A.N.S.P. 13703) comes from the Pleistocene of Quebrada Rabo de Puerco, near Puerto Armuelles, Chiriqui Province, Western Panama, and is named for Mr. Mark Trafton, Jr. who was the first to collect in the Pleistocene beds at this locality •••• “. A copy of the Proceedings, with pictures of Chione Traftoni, is in my library.

Continuar a,en PART 11 of this story.

NOTES:

*All photos, researched from the era, were added by the editor of Visit Puerto Armuelles.

The photo of the Chione collection above is an example of what they look like. I could not find a photo of the ‘Chione Traftoni’ online.

* Until the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores, Chiriquí was populated by a number of indigenous tribes, known collectively as the Guaymí people.