***If you missed the previous installments, click on the links here:

1928: Parte 1, 1928: Parte 2, 1928: Parte 3, 1928: Parte 4, 1929:Parte 5, Parte 6, Parte 7, Parte 8, Parte 9, Parte 10

Regressing a little, Sigatoka (Cercospora musae), a leaf spot disease of bananas, which wiped out entire plantations in the Far East” was discovered in Company plantings in Honduras in 1936. This was a major threat to the banana industry and called for fast action since an effective control had never been developed. Here Sam Zemurray’s confidence in Doc Dunlap as Tropical Research Director paid off. Doc reasoned that since cercospora was a fungus, a fungicide such as Bordeaux mixture (copper sulfate, lime and water) might give effective control.

It had been used on a small scale in France to control a similar leaf spot of grapes, but on bananas, with so many large leaves and so many plants per acre, application presented major problems.

Test plots, using a garden type high-pressure mobile sprayer unit and hose gave good results, but how to make an application of 150 gallons per acre every two or three weeks to over 150,000 acres? Before long, Company engineers, working with the research department, developed a plan involving a large diesel-driven high-pressure pump, two 5,000-gallon wooden mixing tanks, and a large storage area for copper and lime, all in one building to serve a farm of 1,000 acres. A grid of 2-inch, and 3/4″ galvanized pipe, with valves to connect long high-pressure hoses, would be laid out on each farm. Two-men gangs would handle each of the 20 (150-foot) hoses to apply 150 gallons of Bordeaux spray per acre, on a two-week cycle if necessary. But the cost? Zemurray didn’t flinch. A 5,000 acre experimental project was soon installed at a cost of half a million dollars. It worked – and would save United Fruit! The Company then practically cornered the galvanized pipe market and ordered enough diesel engines and high-pressure pumps to install similar systems on all the banana farms in all divisions.

By 1938 surveys showed scattered spots of Sigatoka of varying intensity in all divisions and control plants were installed on a priority basis as fast as equipment could be secured and installed. Chiriqui at the time had the least infection but being such a large division it would take some time to get all the control projects installed.

In February of 1938, Doc Dunlap (my pal from Esperanza days) requested that I make a trip to the Research Department in Honduras to familiarize myself with all aspects of Sigatoka disease and its current control measures. Don Walter Turnbull (General Manager of Tropical Divisions) concurred and advised Mr. Blair. The reason for this was that Doc felt I was the best qualified in the Chiriqui division to become “Superintendent of Disease and Insect Control” when material became available to commence installation of control projects. By this time, I had a secretary in my office who could take over for a while, so around March 1st I went to Honduras (missing Mark Ill’s first birthday party) for indoctrination in Sigatoka disease. This included intensive pathology laboratory study, field observations of disease spread, including trips to the Tiquisate and Bananera divisions of the Company in Guatemala, and working with engineers on details of field installation of control systems.

Returning to Panama from Honduras, I was about due a vacation so we planned Harriet’s and the children’s trip to the States in June followed by mine in August to meet them in South Hanover. I stayed on in the Manager’s office for another 5 months waiting for arrival of materials to install the Sigatoka projects. But in the meantime I made frequent trips to the farms checking on status of disease spread and instructing farm personnel in making surveys.

On March 1st, 1939, I was officially appointed to the new position and took over with some apprehension knowing that if later on the disease got out of control and the farms chopped down, I would be out of a job! I got a raise, to $3,000 a year, and was assigned a motorcar and a “motorboy” to make daily trips to the farms while we continued to live in Puerto Armuelles. I was given two very qualified assistants, Ira Hubbard and Rudy Lunemann from Honduras, and hired another – “Chips” Spence from California – a brother of one of the farm overseers.

Together, and working with construction, engineering and agricultural personnel, we supervised and coordinated work on 30 projects during the next two years and had most of them “spraying” for control of Sigatoka disease (Sigatoka was the name of a valley on the South Pacific island of Fiji where the disease was first described many years ago).

So now I was back on the farms, busy and happy with this new challenge and anxious to prove the confidence that Dunlap and Turnbull, and Blair and Block, had in my ability to do the job.

Field spraying could only be done early in the day, before the winds started up, so I spent many long afternoons checking experimental plots that I had personally laid out in areas of heavy, light, and No Sigatoka disease to satisfy my curiosity about how this leaf spot infection took place. In the course of a year, I determined that infection did not occur, as was supposed, by random wind-borne spores landing on leaf surfaces, but by spores falling into the vortex of unfurling leaves where there was a little water, or enough moisture for them to sporulate. This would cause heavy bands of primary spotting on the tips, centers, or bottom parts of leaves, depending on how much they had opened and the amount of moisture present when airborne spores came in contact with their unfurling surfaces. I repeated these experiments hundreds of times and observed that very little Bordeaux spray, always directed at all open leaf surfaces, actually fell into the vortex of opening leaves.

I confirmed this in my test plots by pouring small amounts of Bordeaux into the vortex of the leaves in areas which had not received the regular spray. It worked! I then figured that smaller amounts of spray applied from above the plants would be much more effective and a lot less expensive. The catch was that airplanes couldn’t possibly carry the large amounts of heavy Bordeaux mixture, so I installed some small thirty-foot pipe risers, fitted with small ‘rainbird’ sprinklers, and connected them to the regular farm Bordeaux grid. These gave good control at a greatly reduced cost, compared to the round hose spray method. A year later, I wrote a paper describing my tests and theory, and sent it to Doc Dunlap. His pathologists took a dim view of this (because they hadn’t thought of it!) and it took a long time to sink in, but I continued my overhead experiments for several more years.

To make a long story short, this idea of mine resulted in my later appointment as Plant Disease and Insect Control Superintendent for all United Fruit Company divisions. And a theory of applying fungicides above the plant led to the use of airplanes and helicopters when micronized fungicides and oil-based sprays were perfected which could be used at rates as low as one gallon per acre, compared to the 150 to 300 gallons of Bordeaux mixture. This method of Sigatoka leaf spot disease control was soon in use on banana plantations world wide and has been ever since. I should have patented my idea!

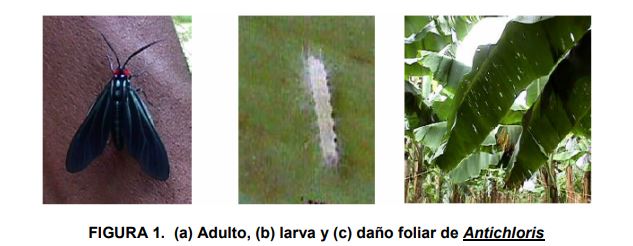

Still another contribution I made to the banana industry was a by-product of my picture-taking hobby. Caterpillars of many different species often caused severe damage to banana plants by feeding on the leaves, and the reduced leaf surface resulted in poor fruit bunch development. Having been interested in butterflies, and moths, I began to photograph the caterpillars, their types of leaf damage, and then hatch them out to photograph the adult forms. Each picture, which I would enlarge if necessary to life size, and color by hand, was then mounted and included with a complete text supported by my records into a book-type report titled “Caterpillar Pests of the Banana”. It is still referred to, forty years later, by entomologists in the banana industry when reporting on related subjects, as well as the control of some caterpillars with insecticides which is now common practice.

That little sideline to my Sigatoka work was responsible for getting the “Insect” into my job title later on, as described above!

Continue to… PART 12 of this story!

NOTES:

*All photos, researched from the era, were added by the editor of Visit Puerto Armuelles.

Mark Trafton’s research is referenced in most banana periodicals about pest control today: “Trafton, M. 1940. Caterpillar pests of the banana: their characteristics and recommendations for their control. Puerto Armuelles, Panamá, Chiriqui Land Company. 20 p.”

*** One of the problems that confronted the production and marketing of bananas on the isthmus was the appearance in 1903 of the disease caused by a fungus known as El mal de Panamá (Black Sigatoka). The banana plants affected by this disease did not produce a fruit for export; Over time these plants withered and died. This was the trigger for the United Fruit Company to abandon its plantations in Bocas del Toro in 1926 and replace them with cocoa and basil production. Banana production was transferred to the Chiriqui province, Puerto Armuelles district, in 1927.

*** The fungus Mycosphaerella fijiensis causes Black Sigatoka, a global problem in modern days, along with Panama Disease. It is forcing banana producers to use more and more chemical pesticides, with all the attendant detrimental effects on the environment.

- Photo credit: “Green Dragon of the Tropics” 1940