If you missed the previous installments:

Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 1

Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 2

Coming to Puerto Armuelles in 1928: Part 3

Part 4 – Esperanza

But there came a time later on when I tired of loosing all my paltry “balboas” (the Panamanian currency) every payday. When I was playing on stage with an orchestra in vaudeville theaters, a friendly magician taught me how to undercut a deck of cards. So, lying on my tijereta at night, gazing through the mosquito netting at the pink eyes of geckos crawling upside down along the thatch “ceiling”, I practiced the “cut” with a deck of cards for hours. Finalmente, I took Bob Cover into my confidence and told him I could deal him an occasional winning hand if he would split the “take” with me. He was all for it, so in one game, after the big-money boys had polished off a lot of beers, while shuffling the deck to deal, I set up a big full house for Bob. The deck was cut and I successfully got it back the way I had it so I could slip Bob’s cards off the bottom. Bob kept raising the pot which grew to a big pile of balboas. It worked! Then, after judiciously letting others win a few, we did it again and wound up with about all the money in the game. There was a lot of hard talk and looks, with hands close to 45’s, but Bob was as tough as they come and he walked safely back to his rancho. In the next game, a week later, we deliberately lost a little in order to stay alive.

Then, Bob and I requested a few days off and rode our mules, saddlebags loaded, some 15 miles through cattle country to Alanje where we caught a railroad motor-coach to David, leaving our mules in a corral with an attendant. The small city of David was the capital of Chriqui province. We spent two days in a small pension and did everything there was to do in town, which wasn’t much, but went through all our winnings in a hurry. My only bring-home purchase was a little portable wind-up record player and a few records. I guess I needed a little music in my jungle habitat although the querulous flute-like calls of the small tinamous at dawn were hard to improve on.

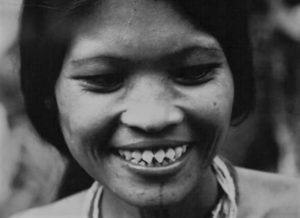

Another diversion, although infrequent, was to ride our mules across the river and then about 8 miles to Divala, a small village of thatched huts. The rain forest gradually gave way to semi-open plains there and the native Chiricanos were small farmers or cowboys on large cattle ranches which supplied the Panama Canal Zone with beef. On special “Saint’s Days” they would celebrate at night with a “dance” in a large manacca shack. The orchestra was an accordionist. We were a big attraction and always welcome guests but had to check our sidearms with the Intendente (a one man police force) and remove our riding boots and spurs before dancing on the dirt floor with the barefoot Chiricana girls.

Another diversion, although infrequent, was to ride our mules across the river and then about 8 miles to Divala, a small village of thatched huts. The rain forest gradually gave way to semi-open plains there and the native Chiricanos were small farmers or cowboys on large cattle ranches which supplied the Panama Canal Zone with beef. On special “Saint’s Days” they would celebrate at night with a “dance” in a large manacca shack. The orchestra was an accordionist. We were a big attraction and always welcome guests but had to check our sidearms with the Intendente (a one man police force) and remove our riding boots and spurs before dancing on the dirt floor with the barefoot Chiricana girls.

They were very short but pleasant and good-looking mestizas with long black hair but with their upper and lower front teeth filed to sharp points. That custom, probably from their tribal Indian forebears, was confined to this rather small part of Panama where it was performed by the mothers, but only on female offspring, once they had acquired their permanent teeth. Of course a few years later their teeth would begin to decay and fallout and the toothless young women, otherwise healthy and cheerful, certainly lost their charm and good looks when they smiled.

Home-made drinks, fruit juices mixed with cheap native rum, were passed out sparingly at the dances but they were sipped slowly and there was little drunkenness. Of course the Intendente kept a sharp eye on the dancers and if a man became loud and tipsy he would be tied up to one of the posts supporting the roof in the middle of the room until the party was over. Cruel punishment, watching all the merrymakers dance around him, not one of whom would speak to him!

The party was over when the accordionist, after one sip too many, could begin to play some awful sour notes and such a terribly confused and mixed-up rhythm that it was impossible to dance. At those dances I often thought of the high-society parties at the Marshall House at York Harbor, Maine, and of the very formal affairs in Cuba at the Banes Club. In Divala I didn’t need a carnet to get a dance with one of those “Indias”‘!

CANTINERA

I must include a little story about one of my riding mules, “Cantinera”. After his six-gun, a woodland overseer’s most valued possession was his riding mule. I had three but my favorite was a small, slick, jet black one, very sure-footed on the rough woodland muddy trails and with a nice even gait. Everyone started calling her Cantinera (barmaid) because after a few of our afternoon trips to the river, and then back to the commissary (our bar!) she refused to go past the “cantina” so I would have to walk the short distance every day from the commissary to the river and back.

When I first acquired Cantinera she took a dim view of me and late one hot morning, at a distant part of the farm, I dismounted to check a contractor’s work. Ordinarily, with the reins hung over its neck, a good mule would stand in one place until the rider was ready to remount. But this time, as I started toward her to remount, she started walking too, about 100 feet ahead of me, for over an ‘hour along a muddy narrow trail, all the way back to the stable in camp. I was hot, and mad. I got into the saddle and rode her as fast as she could go, up and down and around the camp clearing, for a long time – until the poor beast stopped, unable to take another step. It took over a week for her to recover. I felt bad about that but she never walked off and left me again .

I guess her revenge was refusing to go past the cantina, probably reasoning that we were both better off there – she tied up and nibbling on sugarcane (remnants of the old plantation) and me grazing on bacalao and hot beer!

Ted (Edward) Scott

was one of the many characters that appeared in Chiriqui in the early days looking for work. He was a well-educated Australian adventurer seeking his fortune and was assigned as timekeeper on the farm next to mine in Esperanza. We lived in the same small compound of manacca shacks. He interested me with his tales of having been a novice prizefighter back “down under” and of his experiences travelling half around the world before arriving in Panama. He didn’t stay long in our camp because as soon as he had saved a little money he took off for Panama City.

I didn’t hear of him again until some four or five years later when his name appeared as an assistant editor and columnist for the prestigious “Panama American” newspaper. A few years later he was in jail in Panama City for articles he had written about Arnulfo Arias, um candidato presidencial off-and-on e ',en” later president for a short time, accusing him of Nazi tendencies (which were true). After a few months another newspaper reporter wrote an article. accompanied by a picture, about a jail cell in Panama City where Scott had been detained. Scott had written in large letters on the cell wall “Arnulfo Arias es un tijo de puta“.

Not long afterward, Scott was out of jail and Arnulfo was in, just before he was expatriated, and he wound up in the same cell that Scott had been in. The picture was of Scott’s thoughts about Arnulfo only now, Arias had crossed out his name and had written above it “Ted Scott” .

Ted continued with the paper for some time but he became more and more controversial due to criticism of Panamanian politics – which was not good! After another couple of years Arnulfo was back in Panama running again for President, and Scott was out, looking for a newspaper job in some other country.

Many years later, in 1954, a long-time friend of mine, Frank Keany, then assistant manager in Banes, Cuba, sent me a clipping from the “Havana Post“. It was by Edward Scott , a regular columnist for that paper. I quote parts of his column “Interesting if True” for August 11th, 1954 .

“Bulletin by Jungle Wireless“. “Any statement in print involving circumstances which depart from the field of common or garden variety experience produces suspicion, but it may not come immediately to the surface. Sometimes I have referred in this section to incidents in the jungles of Central America and even while I was writing, I knew that there would be some, or many, who would suspect that I was drawing the long bow. But there are others who themselves have rattled around the areas to which I have given attention. They discern a key phrase, or minute but relevant detail, which convinces them that Edward the Unready must have been among those present. When I have spoken about nine-foot jaguars, or “Tigres” as they are known on the mainland, South of the Border, there has been a raising of eyebrows and a mental reflection on the good which could result from the taking of tonic without what goes with it like mint goes with julep”.

“In a discussion I had with Francis X. Keany, assistant manager of the United Fruit Sugar Company at Banes, we were talking about old times and old-timers. The name of Mark Trafton Jr. was introduced. I said I had known Mark Trafton in Chiriqui on the border of Panama and Costa Rica back in 1928 when he was a fresh-faced youngster. Now he is Assistant to Norwood C. Thornton, Director of Tropical Research”.

“In a discussion I had with Francis X. Keany, assistant manager of the United Fruit Sugar Company at Banes, we were talking about old times and old-timers. The name of Mark Trafton Jr. was introduced. I said I had known Mark Trafton in Chiriqui on the border of Panama and Costa Rica back in 1928 when he was a fresh-faced youngster. Now he is Assistant to Norwood C. Thornton, Director of Tropical Research”.

“I well remembered Mark Trafton, with his banana cowboy hat and six-gun. We were about the same age and became quite clubby after we had been introduced in the presence of a case of hot beer and a couple pounds of bacalao and crackers. “sim” I said, waxing warmly reminiscent, “Mark is a really nice bloke. He came straight to Chiriqui from school, but he liked the bush”. “There was a pause while Mr. Keany made up his mind whether it would be proper to contradict me flatly or merely outflank me”.

I think he was here in Cuba before that” he finally said. A few minutes later he had a card in his hand which established that Mark Trafton, Jr. had been employed in Banes as a stenographer on November 13, 1926, and furthermore, he became a full-fledged overseer before he was transferred to Chiriqui, Panama on September 5th 1928″.

As a postscript to the above, as I copy it 28 years later, I might add that Ted Scott in that column in the Havana Post absolves me of “drawing the long bow” if there is any “raising of eyebrows” by readers as they peruse these notes of my experiences as a woodland overseer in Esperanza!

To be continued…

PART 5 of this story: The Transition in 1929

NOTES:

*All photos, researched from the era, were added by the editor of Visit Puerto Armuelles.